Anyone who has explored a family history will know there’s only so much you can learn about long lost relatives. You can gather the facts but then only speculate about the emotions and the motives behind the decisions, the secrets that have been buried, and the truth of stories you may have been told.

Anyone who has explored a family history will know there’s only so much you can learn about long lost relatives. You can gather the facts but then only speculate about the emotions and the motives behind the decisions, the secrets that have been buried, and the truth of stories you may have been told.

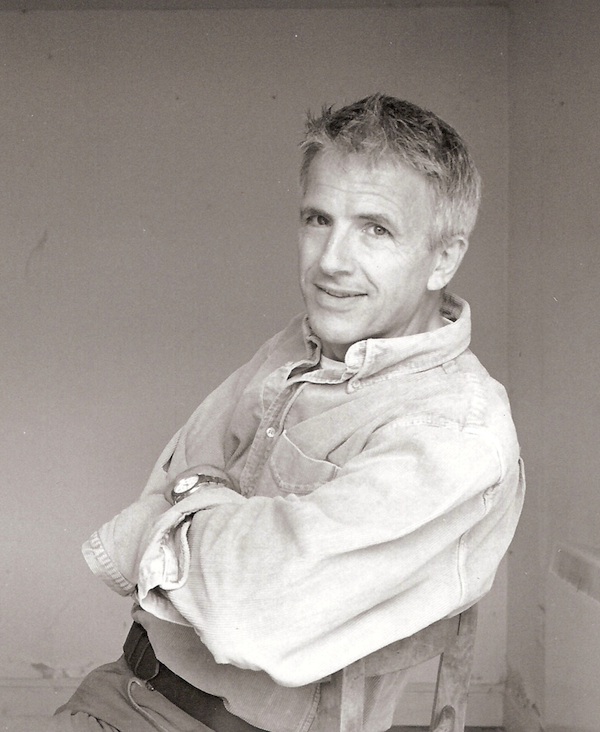

Novelist, Patrick Gale had long been intrigued by the tales surrounding his great-grandfather. Huge bearskin mittens (with claws intact) in the family dressing-up box were said to belong to ‘Cowboy Grandpa’ and prompted accounts of log cabins, fights with Indians and wild animals, and a life in the Canadian west.

But was grandpa really a cowboy? And why did he leave his wife and daughter behind in London, and never send for them to join him in his new life?

“I had never quite bought Granny’s explanations as to why her father left,” says Patrick. “One day she would say, ‘he lost all his money’, but that clearly wasn’t the case because he kept sending money home. Another time she said ‘he was a bit of rogue’, but that wouldn’t wash either because he seemed a very quiet man.”

Then a few years ago Patrick inherited a hoarde of papers – correspondence between his mother and grandmother, and the beginning of a memoir. These provided more details but it was still an incomplete account so Patrick “started to make stuff up”.

“I wanted to honour all the facts but come up with a story that would be emotionally satisfying and wouldn’t give the lie to any of the things that had come down to me through the papers and stories,” he says. “So I ‘gayed’ him up.”

Cowboy Grandpa was Harry Cane, a shy man with a stutter. Living in Edwardian London, Harry inherited great wealth, married, and had a daughter, but then things seemed to go wrong. Harry’s income was halved and the family had to return to live with his in-laws. Shortly after, Harry emigrated to Canada, alone, and became a farmer.

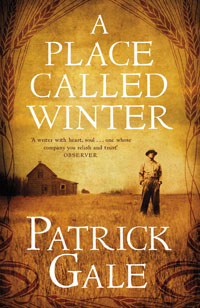

So far, everything is true. But in Patrick’s novel ‘A Place Called Winter’ published last month [March], it is the threat of a scandal and imprisonment over a homosexual affair that causes Harry to flee England for Canada.

“I didn’t plan from the start to make him gay,” says Patrick. “It happened organically and then, in a way, I blended my character with Harry’s to the point where it has now become like a false memory. I had to correct one of my young nieces the other day because she said, ‘Oh, because Great-great Grandpa was gay’ and I had to say, ‘No, I made him gay’.”

This is Patrick’s 17th book and he has a strong female readership, boosted when his book ‘Notes from an Exhibition’ was listed as a title in the Richard and Judy Book Club. This new book, his first historical novel, will have a wide-ranging appeal.

“I think the publishers chose the cover for this book to appeal to men,” he says. “But it is a book full of women.”

Just as Harry fled to Canada, life in the prairies was also an escape route for women who were well brought up but who would never have settled down, never have become ‘good’ wives. One of Patrick’s characters, Petra Slaymaker, a neighbour to Harry, is an amalgam of the characters that he read about at this time at the beginning of women’s suffrage.

“As is always the case, you start a book about ‘this’ and it ends up being about ‘that’,” says Patrick. “The book is about sexuality and gender and the different things that men and women could be at this point of time.”

“As is always the case, you start a book about ‘this’ and it ends up being about ‘that’,” says Patrick. “The book is about sexuality and gender and the different things that men and women could be at this point of time.”

A tremendously sensitive and poignant book, with vivid, captivating characters and powerful scene-setting, it confronts the reality of living and working on the land, the expectations and pressures of society, and the fear and violence of a lawless environment. But it is also a book about Patrick.

“As I was progressing the story, I found I was projecting myself into Harry more and more, trying to understand him. I found myself thinking how I would cope as a gay man in this pre-world war one situation, where I would have had no way of putting my feelings into words.”

Today Patrick lives happily with his partner of 17 years, Aidan Hicks, a farmer in Cornwall, and their life together also informs this book.

“I live on a working farm. I am the unpaid labour but I have done enough to be able to write about Harry and the shock of being a citified gentleman who has never had to lift a sledgehammer, handle barbed wire, put up fencing or dig ditches. I hope I’ve shown that what starts out as punishment becomes something quite meaningful.”

Patrick spent time in Canada exploring the landscape and was reassured to find that Harry’s farm in Saskatchewan is still being cultivated. It is land which is essentially very flat just like Land’s End where Patrick lives, and Suffolk where he is speaking at the Felixstowe Book Festival in June.

“I love East Anglia. I find something completely magical about places with a big horizon,” he says. “On a summer’s evening you see these incredible forty foot shadows with nothing in their way. You just see for miles.”

The huge expanses of land appeal to him. “Writing about Harry’s life, I realized that actually I would have loved it,” he says. “The silence, hearing nothing but the coyotes barking, the occasional bit of bird song. I would have loved hearing nothing but a neighbour chopping wood.”

Catherine Larner